Rosa May Billinghurst

Rosa May Billinghurst was a grand daughter of John Brinsmead, the piano maker. Her mother Rosa Ann Brinsmead married Henry Farncombe Billinghurst, a banker.

Rosa May (known as "May") gained prominence through her activities as a suffragette. At 5 months old, Rosa suffered an illness that left her whole body paralyzed. She later regained the use of her hands and arms but was never thereafter able to walk unaided. In addition, she suffered from chronic hay fever and throat ailments. To get around, she used a special tricycle, which can be seen in pictures of suffragette rallies. She was referred to as "the cripple suffragette"

Rosa Billinghust during a suffragette protest

Rosa Billinghust during a suffragette protest

Rosa was born and raised at 35 Granville Park, Lewisham in South London. She had an older brother, Henry Billinghurst, who went on to become the managing director of the John Brinsmead and Sons Ltd. piano firm, along with three younger siblings; Walter, Alice and Albert (known as "Alf").

It was sister Alice that first widened May's interests. Alice undertook rescue work amongst the poor in London. Accompanying her sister in this work led May to begin work at the Greenwich and Deptford Union Workhouse, an old fashioned poor house for the poor, sick and infirm. She taught Sunday School and worked with The Band of Hope, a Methodist Church temperance organization aimed at helping the children of the poor. The experiences, along with those of her sister, politicized her views. When asked how she became a suffragette, she described how:

My heart ached [for the people she had met] and I thought surely, if women were consulted in the management of the state happier and better conditions must exist for hard-working sweated lives such as these.

It was gradually unfolded to me that the unequal laws which made women appear inferior to men were the main cause of these evils. I found that the man-made laws of marriage, parentage and divorce placed women in every way in a condition of slavery − and were as harmful to men by giving them power to be tyrants.

The arrest of Christabel Pankhurst, in 1907, prompted May to abandon the Liberal Party and join the Women's Social and Political Union, along with her sister Alice and her mother Rosa. She threw herself into political campaigns across the country, noticeably campaigning against a young Winston Churchill in the North-West Manchester riding where he lost to the Conservative candidate, in part because of the suffragette's high profile activities.

May happily exploited the attention her tricycle, decked out in purple, white and green, gave her at suffragette demonstrations. Several press reports noted her colourful and enthusiastic presence at major rallies such as the October 13th, 1908 demonstration outside the House of Commons. In the "Black Friday" demonstration in November, 1910 outside the Commons, where three women protesters died, May was one of the 159 people arrested. The next year, at a demonstration during the opening of parliament, May was arrested again when she used her chair to project herself, full tilt, into the police cordon. The police carried her, tricycle and all to the Cannon Street police station. Not long after, May was arrested again, this time for participating in a "window smashing raid" planned to bring attention to the cause. For this she received one month's hard labour. Her tricycle had proved a useful vehicle for hiding and transporting bricks to throw, since few policemen wanted to search a crippled woman in a wheelchair.

May was asked along with others to attend a meeting and describe here experiences. She testified:

I am lame cannot walk or get about at all without the aid of a hand tricycle, and was therefore obliged to go to the deputation riding on the machine. At first the police threw me out of the machine onto the ground in a very brutal matter. Secondly, when on the machine again, they tried to push me along with my arms twisted behind me in a very painful position, with one of my fingers bent right back, which caused me great agony. Thirdly they took me down a side road and left me in the middle of the hooligan crowd, first taking all the valves out of the wheels and pocketing them, so that I could not move the machine, and left me to the crowd of ruffs, who, luckily, proved my friends. Another time, the police, in addition to the personal violence, finding that they could not remove the new valves, twisted my wheel so that it was again impossible to move the machine. In this plight they left me again, first telling a man in the crowd to slit my tire down with a policeman's knife. This, the man refused to do, and the policeman was prevented doing any further injury by a gentleman taking his number. I may also add my arms and back was so badly bruised and strained by the rough treatment of the police that for two days after Friday 18th I could not leave my bed.

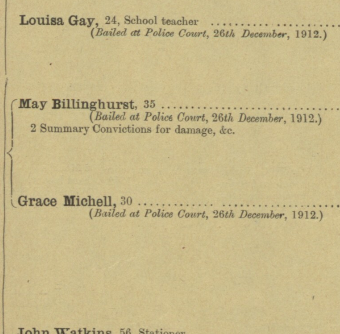

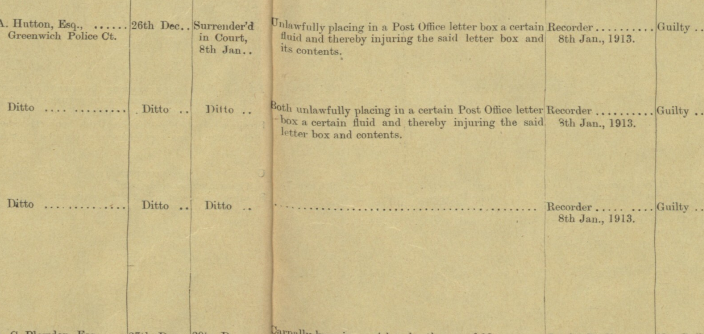

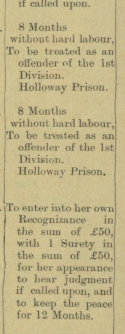

Once released, May resumed and escalated her activities, joining the secret campaign to destroy the contents of pillar [mail] boxes by pouring paint over the contents. She was caught at this in December of 1912 and committed for trial at the Old Bailey where she was convicted after conducting her own defense, and sentenced to eight months in Holloway Prison.

May Billinghurst's Conviction for Postbox Bombing - found guilty and sentenced to eight months in prison

May Billinghurst's Conviction for Postbox Bombing - found guilty and sentenced to eight months in prison

There, she, like others, engaged in a hunger strike, although for her this was a very significant step due to her medical conditions. It took three doctors and five wardresses to force feed her, which, as she hoped, caused a public outrage. Letter writing campaigns were undertaken and questions asked about her case in the House of Commons. She was soon released and after a brief recovery period was given a position of honour, sitting beside Mrs. Pankhurst at a February 4th meeting.

Throughout, May received support from her family. The family home took in suffragettes let out on bail hoping to evade re-arrest. In the last big suffragette demonstration before the outbreak of World War One, May projected her tricycle towards the line of mounted policemen. After that, she chained her tricycle to the railings outside Buckingham Palace, but even with all that provocation failed to get herself arrested again.

Rosa May Billinghurst camping with Kibbo Kift

Rosa May Billinghurst camping with Kibbo Kift

In 1922, May moved in with her artist brother Alf near Regent's Park. She obtained a car and was able to drive. She became an active participant in the Kibbo Kift movement, an outdoor activities group, open to males and females, set up in contrast to Baden Powell's Boy Scouts. She attended Mrs. Pankhurst's funeral and the unveiling of her statue, still located just behind the House of Commons, in 1930.

In 1939 she moved to Weybridge, Surrey where she lived until her death on September 4th, 1953. A suffragette colleague, Lilian Lenton wrote an obituary containing the following thought:

Despite her frustrating affliction I have known her always as full of life and courage, not to mention jollity, not bitter as she might have been, sustained, I think, by her belief in re-incarnation. She thought of this life as but one of many. She hoped for and expected better luck next time, and this, I trust, will be hers.

A testament to Rosa May Billinghurst's importance to the British Women's Suffrage Movement is her selection as one of only ten women selected as the subject of a chapter in the 2003 book Freedom's Cause − Lives of the Suffragettes by Fran Abrams, Profile Books. Much of the information in this biography comes from that excellent chapter, which also includes additional material on her family life. It is well worth a read.